Just published the first chapter of my PhD on remote fossil site detection using satellite images and unsupervised learning in PeerJ.

d’Oliveira Coelho J, Anemone RL, Carvalho S. 2021. Unsupervised learning of satellite images enhances discovery of late Miocene fossil sites in the Urema Rift, Gorongosa, Mozambique. PeerJ 9:e11573 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.11573

It is open acess and available at https://peerj.com/articles/11573/?td=bl

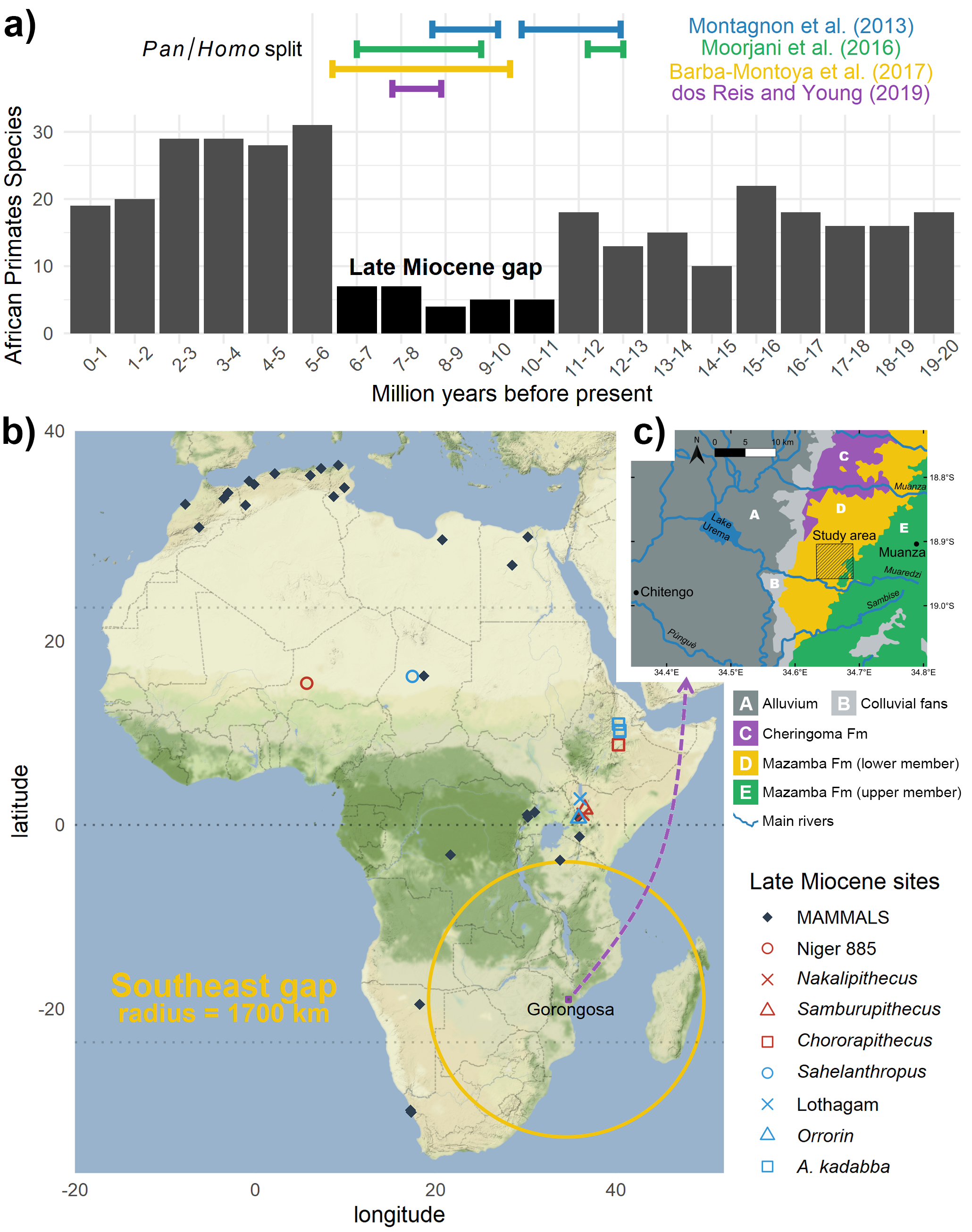

The paper starts by exploring the spatial and temporal gaps of the primate & hominid fossil record of Africa in the late Miocene. The Gorongosa National Park in Mozambique is shown to be a strategic location, with great potential to fill some major gaps in paleoanthropology.

We also discuss the difficulties of surveying for new paleontological localities, specially within modern forests/woodlands as in Gorongosa, since dense vegetation cover reduces visibility (i.e. finding clues in topography and landscape).

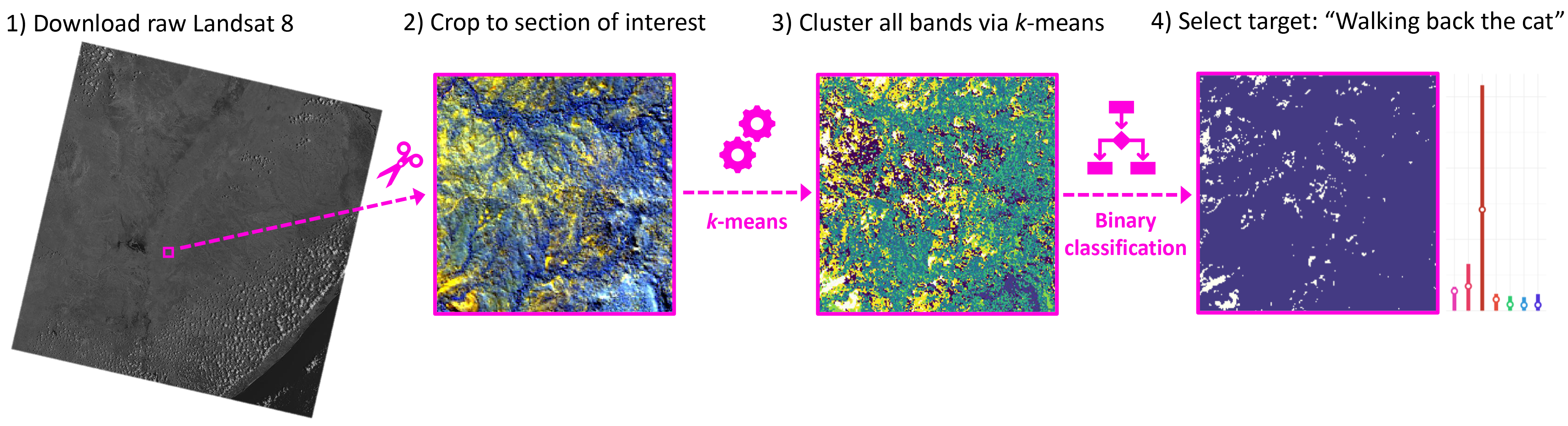

To increase the chances of a successful discovery of fossil sites, we introduced an algorithmic pipeline. 1) Download Landsat 8 satellite image ➜ 2) crop image to study area ➜ 3) clustering algorithm ➜ 4) binarize clusters and calculate variable importance using randomForest

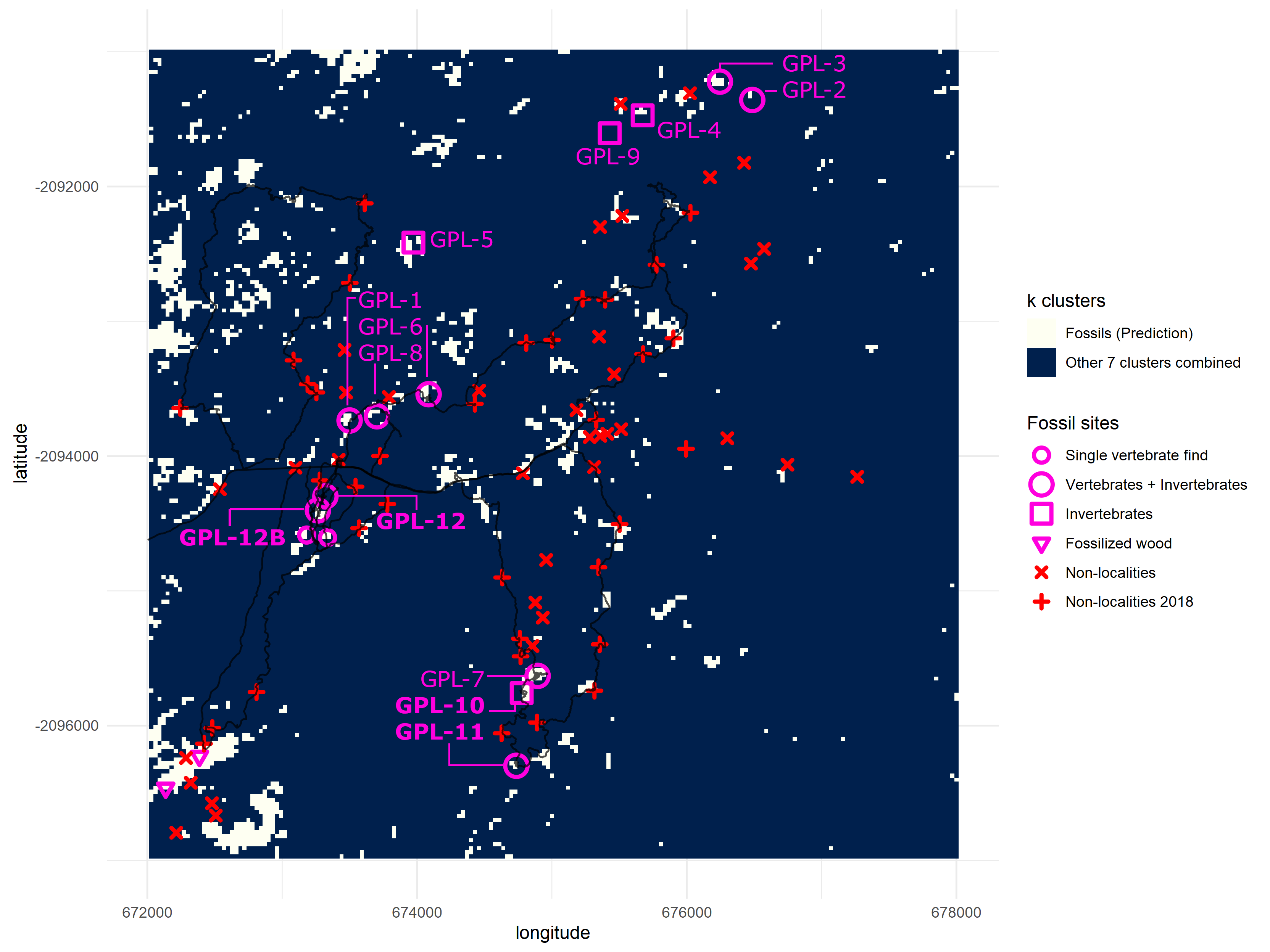

4 new fossil sites were discovered in Gorongosa National Park using this approach. Overall accuracy of the binarized k-means clusters was ~ 85%. This indicates the high potential of our remote sensing pipeline for exploratory paleontological surveys.

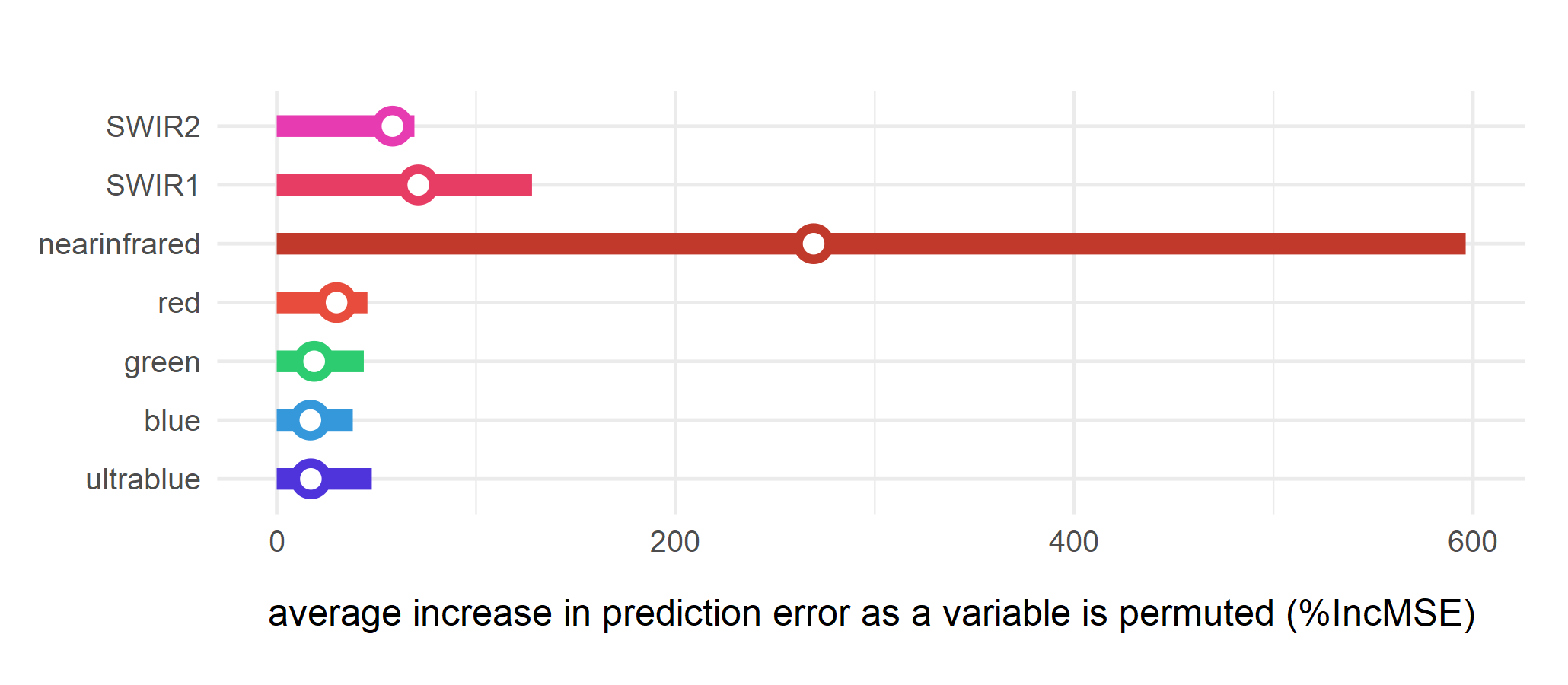

Relative importance of spectral bands for clustering was determined using the randomForest algorithm, and near-infrared was the most important variable for fossil site detection, followed by other infrared bands. The visible spectrum did a poor job as an indicator of fossil sites.

This tool can be used for locating new fossil sites. In Gorongosa, the discovery of the first estuarine coastal forests of the East African Rift System (EARS) fills an important paleobiogeographic gap of Africa. The new sites will be key for testing hypotheses of primate evolution in such settings.

Abstract

Background

Paleoanthropological research focus still devotes most resources to areas generally known to be fossil rich instead of a strategy that first maps and identifies possible fossil sites in a given region. This leads to the paradoxical task of planning paleontological campaigns without knowing the true extent and likely potential of each fossil site and, hence, how to optimize the investment of time and resources. Yet to answer key questions in hominin evolution, paleoanthropologists must engage in fieldwork that targets substantial temporal and geographical gaps in the fossil record. How can the risk of potentially unsuccessful surveys be minimized, while maximizing the potential for successful surveys?

Methods

Here we present a simple and effective solution for finding fossil sites based on clustering by unsupervised learning of satellite images with the k-means algorithm and pioneer its testing in the Urema Rift, the southern termination of the East African Rift System (EARS). We focus on a relatively unknown time period critical for understanding African apes and early hominin evolution, the early part of the late Miocene, in an overlooked area of southeastern Africa, in Gorongosa National Park, Mozambique. This clustering approach highlighted priority targets for prospecting that represented only 4.49% of the total area analysed.

Results

Applying this method, four new fossil sites were discovered in the area, and results show an 85% accuracy in a binary classification. This indicates the high potential of a remote sensing tool for exploratory paleontological surveys by enhancing the discovery of productive fossiliferous deposits. The relative importance of spectral bands for clustering was also determined using the random forest algorithm, and near-infrared was the most important variable for fossil site detection, followed by other infrared variables. Bands in the visible spectrum performed the worst and are not likely indicators of fossil sites.

Discussion

We show that unsupervised learning is a useful tool for locating new fossil sites in relatively unexplored regions. Additionally, it can be used to target specific gaps in the fossil record and to increase the sample of fossil sites. In Gorongosa, the discovery of the first estuarine coastal forests of the EARS fills an important paleobiogeographic gap of Africa. These new sites will be key for testing hypotheses of primate evolution in such environmental settings.